The Art of Yuzen and Freehand Painting on Silk

Within the rich tapestry of Japanese textile arts, few techniques have captured the imagination and admiration of artisans quite like the sophisticated methods of decorating silk fabric through painting and dyeing. Two distinct yet complementary approaches emerged from this tradition: the meticulous paste-resist technique of yuzen painting and the spontaneous artistry of freehand painting. These methods represent different philosophical approaches to textile decoration, each offering unique aesthetic possibilities and requiring distinct sets of skills, yet both contributing to the extraordinary legacy of Japanese silk artistry.

The Revolutionary Invention of Yuzen

In the long and eminent story of the kimono, the technique that the Japanese are most deservedly proud of is the home-grown innovation of yuzen resist painting. The invention of the yuzen technique in late 17th century Japan marked a momentous occasion in the history of patterned textiles, a breakthrough that would fundamentally transform how intricate designs could be applied to fabric. Despite its revolutionary nature, this technique remained broadly ignored in the world outside of Japan until the second half of the 20th century, when international appreciation for Japanese craftsmanship finally began to flourish.

The significance of yuzen cannot be overstated, for with this technique, it became possible to express an artist's vision in both color and intricacy on silk or cotton with precision akin to painting on canvas. This represented a quantum leap in textile decoration, allowing for levels of detail and color complexity that had previously been impossible to achieve on fabric. The technique opened new realms of artistic expression, enabling craftsmen to create textile masterpieces that rivaled traditional paintings in their sophistication and beauty.

This revolutionary painterly technique received its name from its brilliant inventor, the monk-artist Miyazaki Yuzen, who developed the process in the late 17th century. Some historians suggest that the impetus for the creation of this technique arose when the Meiji shogunate imposed restrictions on extravagant clothing featuring shibori tie-dyeing and elaborate embroidery. Whether prompted by such governmental regulations or driven by pure artistic innovation, it became immediately obvious that yuzen dyeing—what might more accurately be described as "yuzen painting"—quickly gained widespread popularity after its discovery and has since become arguably the most famous and celebrated of all Japanese dyeing techniques.

For custom, high-end haori jackets, yuzen painting (also known as "tegaki yuzen" or yuzen dyeing) emerged as the most popular and prestigious decoration technique. This specialized paste-resist painting method truly exemplified the pinnacle of Japanese craftsmanship, representing centuries of refinement in both technical skill and artistic vision. The technique allowed Japanese artists to create intricate designs with vibrant colors on silk or cotton, achieving levels of precision that closely resembled painting on canvas while maintaining the unique qualities inherent to textile art.

The Intricate Yuzen Process

The yuzen process itself is a masterclass in methodical artistry, requiring patience, skill, and an intimate understanding of how dyes interact with silk fibers. The initial stage involves stretching the kimono or haori fabric carefully on a wooden frame to ensure proper tension and prevent distortion during the painting process. The artist then draws the desired pattern using non-permanent blue vegetable dye, creating guidelines that will disappear during subsequent processing stages.

Following the preliminary sketch, the artist applies a resist paste called "nori," typically made from rice paste, which serves as a barrier to outline the design and prevent dyes from spreading into unwanted areas. This crucial step requires extraordinary precision, as the quality of the final design depends heavily on the accuracy and consistency of these resist lines. The paste must be applied with steady hands and careful attention to detail, as any inconsistencies will be magnified in the final product.

Once the resist paste has thoroughly dried, the true artistry begins. Dyes are carefully painted within the outlined areas using fine brushes specifically designed for textile work. This stage demands not only technical skill but also artistic vision, as the artist must understand how colors will interact with the silk fibers and how they will appear once the process is complete. The painting requires multiple layers and careful color building to achieve the desired vibrancy and depth.

When the painting phase is completed, the fabric undergoes steaming to set the colors permanently into the silk fibers. This critical step ensures that the colors will remain vibrant and stable over time. As a final step in the process, the starch paste is carefully washed away, revealing the intricate designs with their characteristic sharp, clean lines and complex color separations that define yuzen work.

The laboriousness and extraordinary level of artistry involved in the yuzen process resulted in garments that were relatively expensive, making them accessible primarily to those of considerable means. During the early 20th century, traditional yuzen dyeing was predominantly reserved for the most formal kimonos, including uchikake (formal wedding over-kimono), furisode (long-sleeved kimono for unmarried women), and tomesode (formal kimono for married women). Due to the labor-intensive nature and the exceptional artistic skill required, yuzen-painted haori commanded premium prices and were considered luxury items of the highest order.

The Freedom of Freehand Painting

In contrast to the structured, methodical approach of yuzen, freehand painting on silk (known as tegaki-zome) represents a more spontaneous and intuitive approach to textile decoration. This technique involves using brushes and dyes or indelible pigment inks applied directly to the silk fabric, without the constraints of resist paste outlines or predetermined patterns. Artists working in this medium draw designs freely, relying entirely on their skill, creativity, and artistic intuition to achieve the desired outcome.

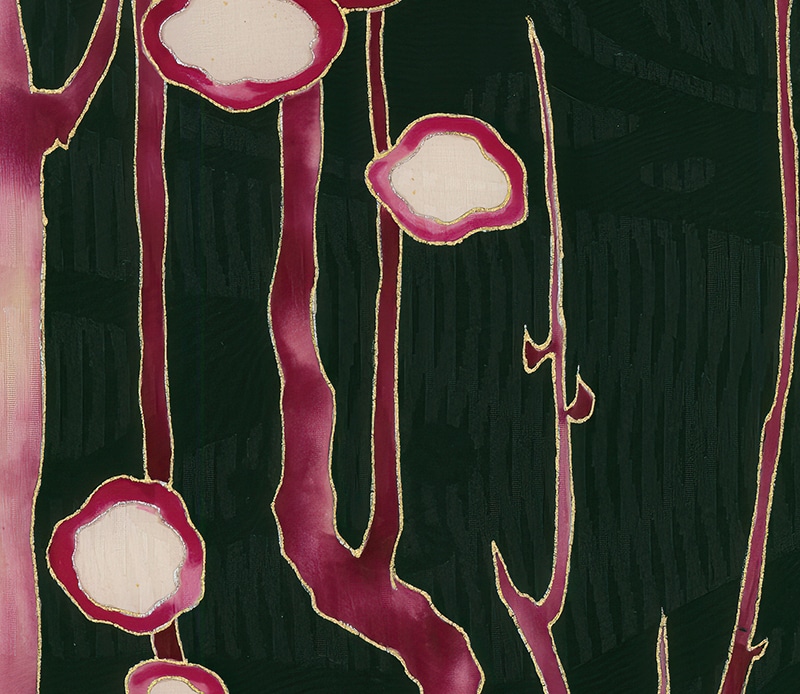

The process begins with silk fabric stretched taut on a frame, similar to yuzen preparation, but from this point forward, the artist works with complete freedom. Using a variety of brushstrokes, artists apply dyes or paints directly to the silk surface, blending colors and creating gradients as inspiration strikes. This method allows for extraordinary spontaneity and fluidity in the design process, ensuring that each piece possesses a unique and deeply personal character that cannot be replicated.

Freehand painting on silk can produce an remarkable range of artistic styles, from abstract expressionist works to highly realistic representations of nature. The designs created through this method are often characterized by their flowing lines and organic shapes, qualities that emerge naturally from the free-flowing application of dyes to silk. The technique allows artists to capture movement and emotion in ways that more structured methods cannot achieve, creating textiles that seem to breathe with life and energy.

Artistic Characteristics and Cultural Significance

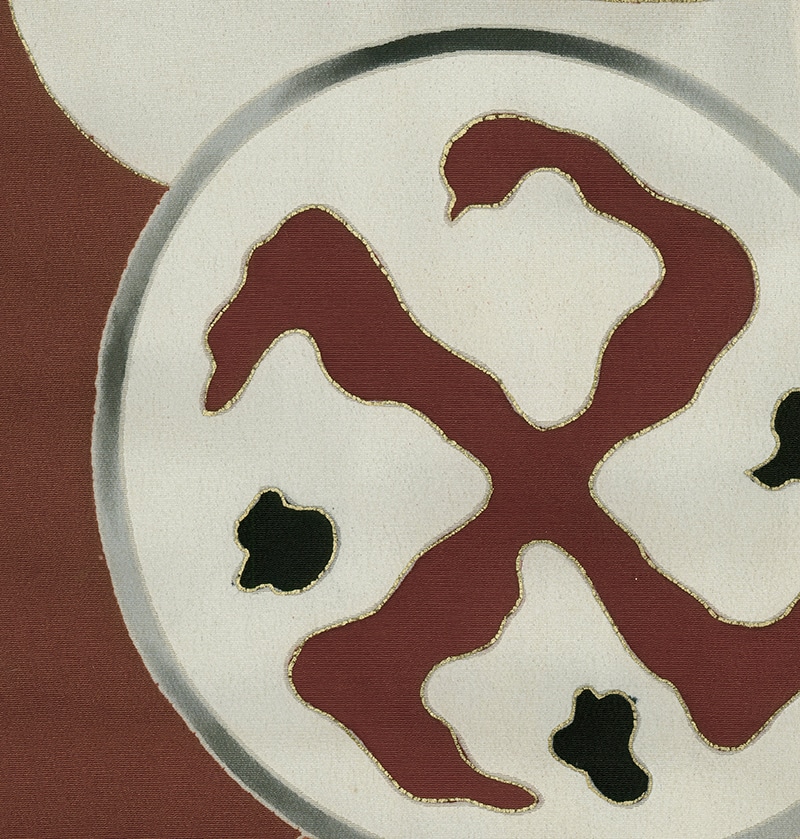

The visual characteristics of yuzen and freehand painting represent two distinct aesthetic philosophies within Japanese textile art. Yuzen designs are typically extraordinarily detailed and intricate, featuring sophisticated motifs such as seasonal flowers, elegant birds, sweeping landscapes, and traditional Japanese patterns that have been refined over centuries. The use of resist paste allows for sharp, clean lines and complex color separations that give yuzen work its characteristic precision and formal beauty.

Freehand painting, by contrast, embraces a more organic and expressive approach. The absence of resist barriers allows colors to flow and blend naturally, creating subtle gradations and soft transitions that give freehand work its characteristic fluidity and emotional resonance. This technique often captures the essence of subjects rather than their precise details, emphasizing mood and atmosphere over technical precision.

Both techniques require exceptional skill and years of training to master, but they demand different types of artistic sensibility. Yuzen artists must possess extraordinary patience and technical precision, along with the ability to envision complex designs and execute them flawlessly over extended periods. Freehand painters, while also requiring technical skill, must additionally possess the confidence and artistic vision to work spontaneously, making irreversible decisions in real-time as they apply dyes to silk.

The cultural significance of both techniques extends far beyond their technical achievements. They represent the Japanese aesthetic principles of beauty, craftsmanship, and artistic expression that have been refined over centuries. These techniques embody the Japanese concept of "shokunin"—the craftsman's spirit of dedication to perfecting one's art—and continue to inspire contemporary artists who seek to honor traditional methods while exploring new possibilities for creative expression.

The legacy of yuzen and freehand painting techniques continues to influence textile artists around the world, as appreciation for these sophisticated methods has finally gained international recognition. These techniques represent not just methods of fabric decoration, but complete artistic philosophies that continue to evolve while maintaining their essential character and cultural significance.

.avif)