Bound by Tradition: The Art of Shibori in Historic Japanese Garments

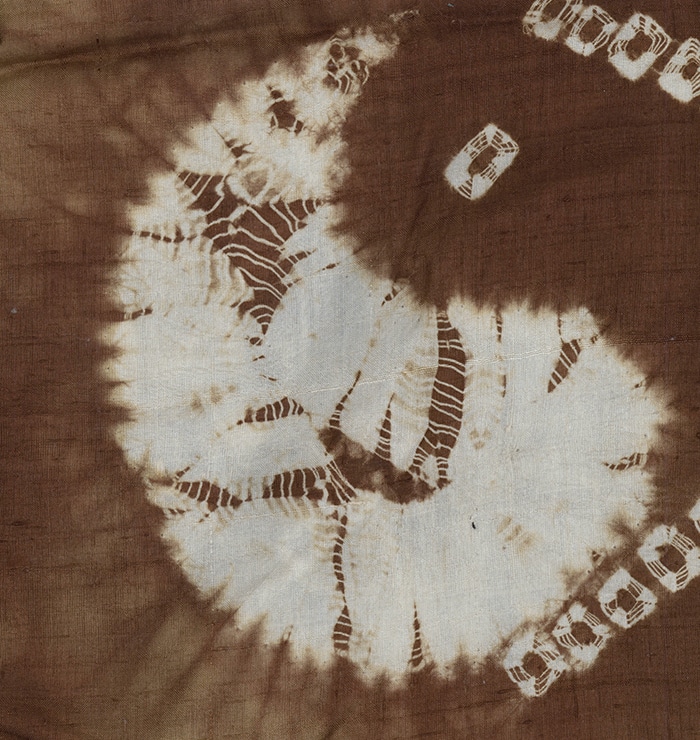

Shibori is an umbrella term derived from the verb root "shiboru" meaning "to wring, squeeze, or press," which refers to various techniques used in Japan to decorate textiles by manipulating the fabric and securing it before dyeing. The fabric is folded, twisted, bound, or compressed in different ways to prevent the dye from reaching certain areas. When the fabric is dyed and the resist material removed, it reveals intricate and irregular patterns that are characteristic of shibori.

While the Japanese term "shibori" is commonly translated into English as "tie-dye," a more precise translation would be "shaped resist dyeing." This term better captures the technique's essence, which involves manipulating the two-dimensional cloth surface into three-dimensional shapes before dyeing by compressing them. The process involves reserving areas by tying, either the pattern areas (patterns left white), or alternatively, most of the background (patterns left colored). Shibori is one of Japan's paste resist techniques, alongside yuzen, stencil dyeing and kasuri.

Shibori made its way to Japan from China about 1300 years ago but only became popular during the Edo period (1603 – 1868). One reason for the delayed popularity of shibori in Japan was the economic aspect. Cotton and silk were expensive materials at that time. In contrast, hemp, which was abundantly available in Japan, served as a more cost-effective alternative for creating textiles. The affordability of hemp made shibori an attractive method for reviving old clothes and giving them a new lease of life. Moreover, social norms played a role in promoting shibori among the masses. The lower classes in Japanese society were forbidden from wearing silk garments. Even if they managed to acquire silk clothing, they were restricted from wearing it. This restriction led to an increased interest in shibori among these social groups as it provided them with a means to decorate their clothing without violating societal norms.

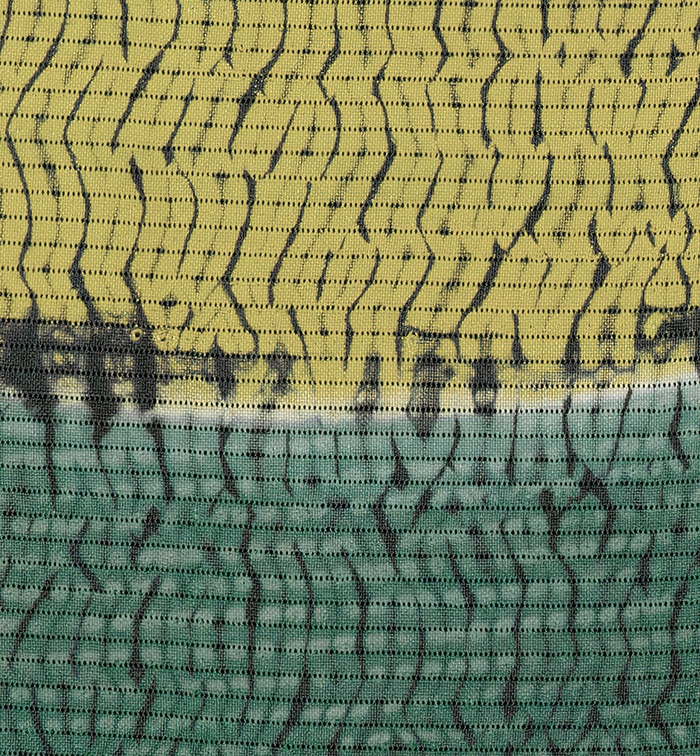

The era of Tokugawa peace saw a flourishing of various arts, including shibori, which diversified into distinct techniques and regional variations. This evolution led to two primary branches of shibori: one focused on embellishing silk for aristocratic kimono production in Kyoto and another as a folk art with unique expressions across different areas.

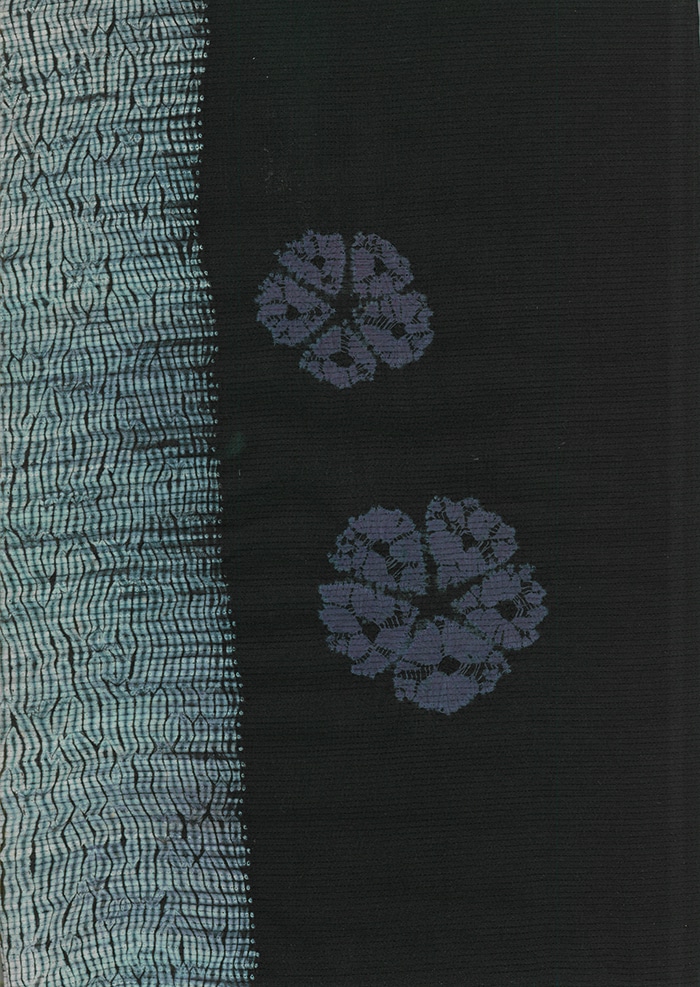

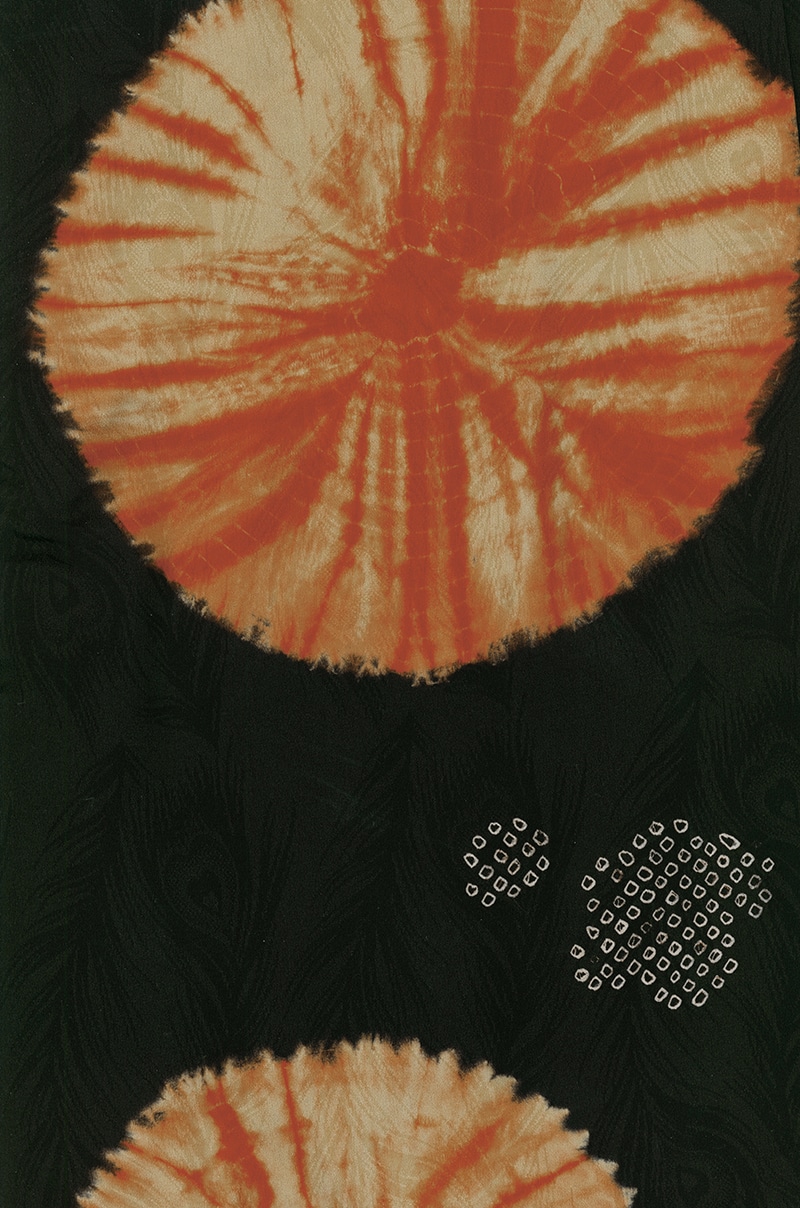

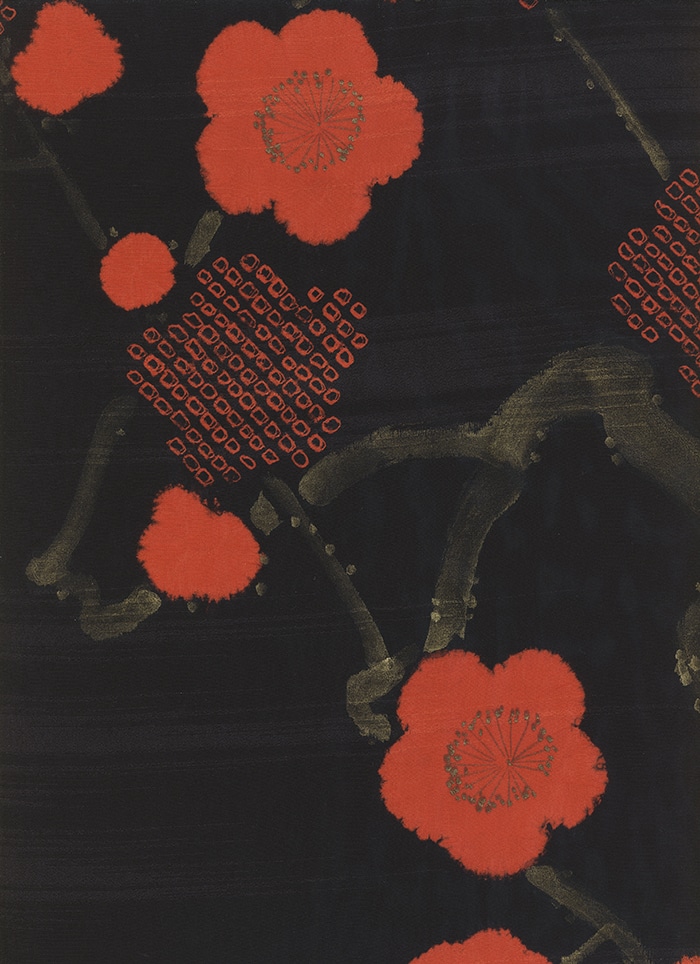

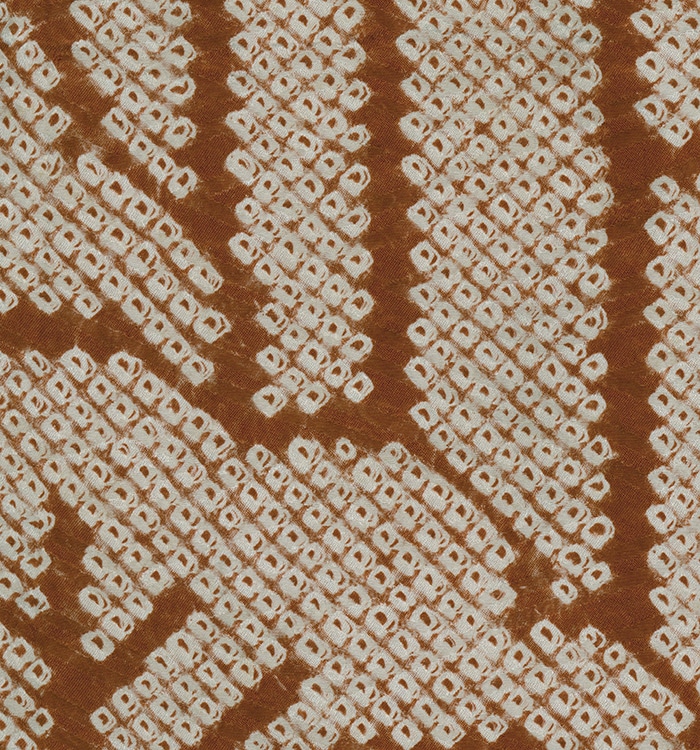

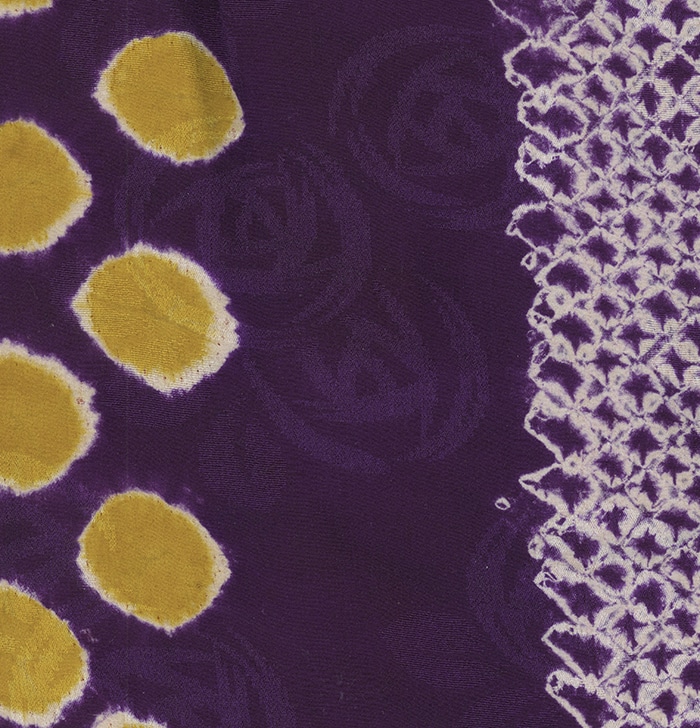

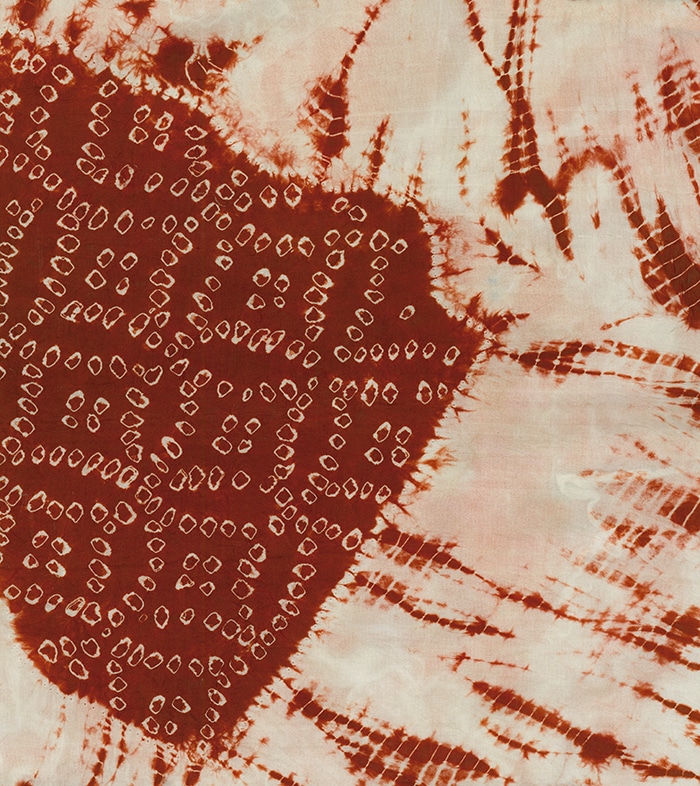

There are many types of shibori, the most popular being 'kanoko shibori' ('fawn-spot shibori'), created by initially tying off numerous closely spaced tiny areas of cloth in diagonal rows, creating a complex dot pattern whose overall greater shape is dictated by the artisan. Shibori artists employ a technique that involves using threads to isolate numerous small, repetitive points on the fabric. This meticulous approach results in designs that are notably more intricate and detailed compared to modern tie-dye creations. The kanoko shibori pattern was so popular, that in order to create the effect more affordably, a stenciled technique kanoko imitation named 'suri hitta' was introduced as early as the Edo period, a style that remained popular during the Taisho and early Showa periods.

Shibori resist stands out for its characteristic soft or blurry-edged patterns, a stark departure from the precise edges produced by techniques like kata-yuzen (stenciling), yuzen painting and embroidery. Unlike these methods, where the artist exerts control over the materials, shibori involves a more cooperative approach where the dyer works alongside the fabric to unleash its full potential. This symbiotic relationship often results in surprising and unpredictable designs that add an element of spontaneity and creativity to the art form.

Despite the fact that expert shibori artisans achieve a considerable degree of control over the shibori process, as one might expect, tying off areas of cloth and immersing it in a dyebath is fraught with uncertainties and risks. The tiny to not-so-tiny imperfections that result -- mostly involving small dye bleeds -- are part of the expected outcome and are considered endearing. This fits well into the old Japanese aesthetic philosophy of wabi-sabi, which embraces imperfection, transience, and the beauty of natural processes.

.avif)