Sacred Threads: The Art and Meaning of Boys' Miyamairi Kimonos

Boys' ceremonial miyamairi kimonos represent some of the most sophisticated and symbolically rich garments in Japanese culture. These unique ceremonial robes, created specifically for an infant's milestone visits to Shinto shrines, embody both artistic excellence and profound cultural meaning. While structured like formal adult kimonos, miyamairi garments feature distinctive family crests and pictorial designs achieved through resist painting techniques like tsutsugaki or pure hand-painting methods. The Japanese regard these ceremonial kimonos as genuine works of art, comparable to paintings, yet despite their remarkable textile artistry, they have received surprisingly little attention from collectors and scholars. This examination focuses specifically on the tradition of boys' miyamairi kimonos and their cultural significance.

Historical Origins and Cultural Context

The miyamairi kimono tradition emerged as a cultural response to Japan's historically high infant mortality rates. The broader customs surrounding special children's garments can be traced back to the 9th century Heian period, when aristocratic families celebrated their children's survival through early childhood years. In traditional Japanese society, where prosperity was believed to stem from long family lineages and numerous offspring, child mortality presented a significant cultural challenge. Many children did not survive their first year of life, prompting the development of elaborate rituals conducted at auspicious moments during childhood to ensure good fortune and longevity.

According to traditional beliefs, newborns were considered impure and unpredictable, initially wrapped in makeshift clothing fashioned from their mother's old garments. On the seventh day after birth, the child would receive a proper name and their first kimono, marking their formal entry into the world. The miyamairi kimono makes its debut when a boy reaches 31 days old during the Hatsu Miyamairi, or first shrine visit. Since the infant is too small to wear the oversized garment, it is draped over him during the ceremony. The kimono is worn again at ages three and five during the Shichigosan ceremony, when the boy is large enough to wear it, though often with temporary alterations to fit his smaller frame.

The Shichigosan ceremony, literally meaning "seven-five-three," focuses on these specific odd-numbered ages because Japanese folk beliefs, influenced by Chinese yin-yang philosophy, consider odd numbers sacred and fortunate.

Ceremonial Significance and Family Traditions

The Hatsu Miyamairi ceremony marks the first formal use of the miyamairi kimono in a boy's life. Traditionally, the father's parents commissioned and purchased this expensive garment, presenting it to their grandchild and his parents as a significant investment in the child's future. The ceremony brings together parents, grandparents, and close family friends in a meaningful celebration.

During the ritual, the paternal grandmother holds the month-old infant while the ceremonial kimono is draped over the tiny baby, with its ties secured around her neck and shoulders. This arrangement serves dual purposes: it supports the recovering mother while symbolically representing the baby's acceptance into the father's family. A Shinto priest, dressed in full traditional regalia, officiates the proceedings by swinging a decorated sakaki branch and offering prayers for the child's happiness and health. The priest invokes the local deity's blessings and purification while reciting a prayer that includes the baby's name, parents' names, family address, and birth date, formally establishing the child as a shrine parishioner.

The ceremony concludes with family members approaching the altar individually, bowing and placing sacred branches as offerings. Grandparents typically host a celebration afterward, then carefully store the miyamairi kimono until the next formal temple visit for the three-year-old Shichigosan ceremony.

The Shichigosan Celebrations

Shichigosan takes place on November 15th, coinciding with a festival honoring a Shinto guardian spirit. This date aligns with the lunar calendar's autumn harvest season and is considered the year's most auspicious day. For three-year-old boys, Shichigosan marks the kamioki event, when they are first permitted to grow their hair. Before this milestone, boys' heads are kept shaven based on the belief that hair attracts diseases and negative energy during the first three years of life. This hair-growing ritual represents a significant transition from infancy to early childhood, symbolizing new developmental phases and increasing maturity.

The five-year-old Shichigosan ceremony continues the tradition of seeking blessings for continued good fortune and longevity. A notable aspect of this celebration is the hakamagi-no-gi, during which the boy wears his first hakama, marking his transition into a more mature role. This milestone designates him as a "little man" for the first time, symbolizing growth and new responsibilities.

Evolution of Design and Construction

The distinction between boys' and girls' kimono designs did not emerge until the early 19th century, becoming more pronounced during the Meiji period (1868-1912) when Japan underwent significant social and cultural transformation. This era also saw the miyamairi kimono tradition spread beyond aristocratic circles to encompass broader segments of Japanese society.

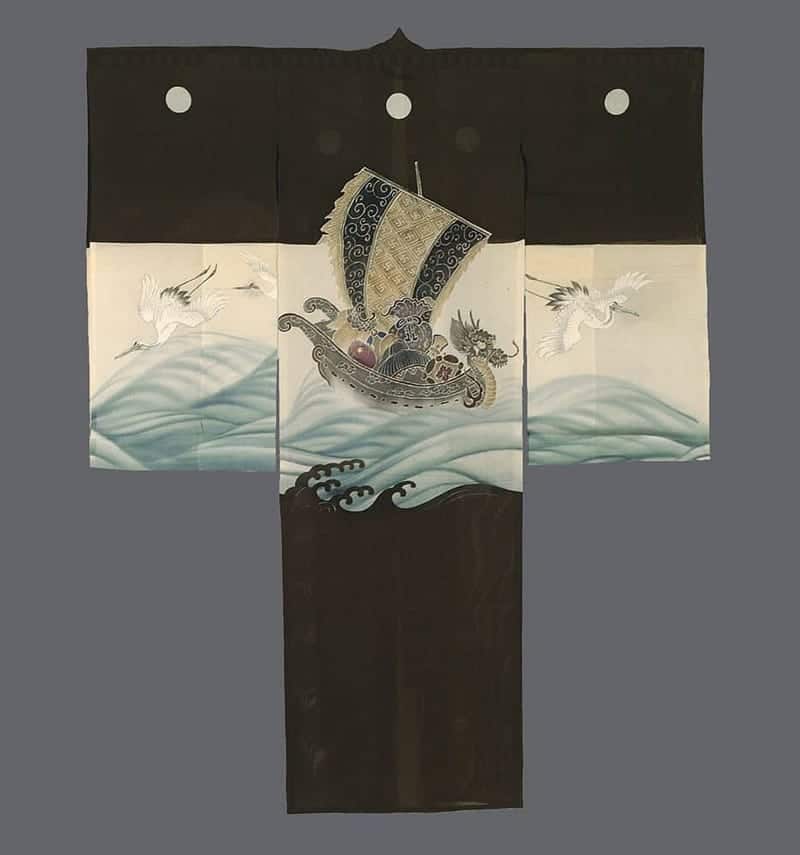

Boys' miyamairi kimonos from the Meiji, Taisho, and Showa periods share consistent structural characteristics with all kimonos: a T-shaped, straight-lined robe extending to the ankle, featuring attached collars and long, wide sleeves. These garments typically display a centered design stretching from sleeve to sleeve. Unlike adult kimonos constructed from two joined fabric strips for the back, miyamairi kimonos are called "hitotsumi," referring to their single-width back panel. Shoulder widths average 33 inches, with overall heights ranging from 37 to 44 inches.

Two simple silk sashes attach to each front lapel, allowing the kimono to be tied closed or secured around the grandmother's neck during the first shrine visit. While adult kimonos utilize crepe and damask silks, boys' miyamairi kimonos require a more reflective plain weave called "habutae," made from the finest silk. Decorative elements are executed through either tsutsugaki yuzen (rice paste resist painting) or tegaki-yuzen (freehand painting). These garments always feature five white mon (family crests) from the father's lineage: three on the upper back and two on each front shoulder, marking them as the most formal of garments.

Unlike the varied colored garments of earlier generations, most boys' miyamairi kimonos from the Meiji, Taisho, and Showa periods feature black backgrounds, though blue or dark brown backgrounds occasionally appear. Recent generations have embraced additional color options.

Protective Elements and Spiritual Significance

Although miyamairi kimonos were created in specialized workshops, mothers often added protective stitching called "semamori" or "back magic" to their sons' garments. Since miyamairi kimonos are hitotsumi (single cloth width) without center-back seams, they were considered vulnerable to harmful spirits. These protective elements, also known as "back guards," complement the auspicious symbols decorating the kimono's surface.

The tradition of using hanging protective threads passed down through generations stems from ancient superstitions attributing protective powers to these elements. The tassels (lowest free-hanging threads) provided symbolic means for parents to grasp and protect their children from being taken by evil forces. The stitching patterns down the back also indicated gender: straight lines of paired dots and stitches, along with diagonal lines running left rather than right, marked garments intended for boys.

Additional hand-sewn protective symbols appear on the kimono's front where the ties meet the forward edge. These range from simple to elaborate designs, all serving the same purpose: providing comprehensive protective coverage for the child. In an era when childhood mortality was common, parents utilized every available source of good luck talismans to safeguard their sons.

Symbolic Motifs and Cultural Storytelling

The inclusion of symbols, folktales, and legendary figures on boys' miyamairi kimonos adds layers of storytelling and cultural significance to these ceremonial garments. Boys' kimonos commonly featured motifs representing strength, honor, knowledge, and perseverance. Popular designs included predatory animals, samurai warriors, war implements, arrows, helmets, and swords. These symbols reflected parents' and grandparents' hopes and aspirations for the boy's growth and future success, transforming each garment into a canvas of dreams and cultural values.

.avif)