From Silk Scraps to Haute Couture: The Rise and Fall of Meisen Kimono and haori

The advent of meisen revolutionized the kimono and haori industry in Japan during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This refers to an inexpensive, thickly-woven and glossy fabric with a stiff drape, produced from reeled low-quality silk, with the patterns possessing the slightly blurred appearance of very complex kasuri. Meisen was known for its affordability, thick texture, and glossy appearance, which made it accessible to a growing middle class.

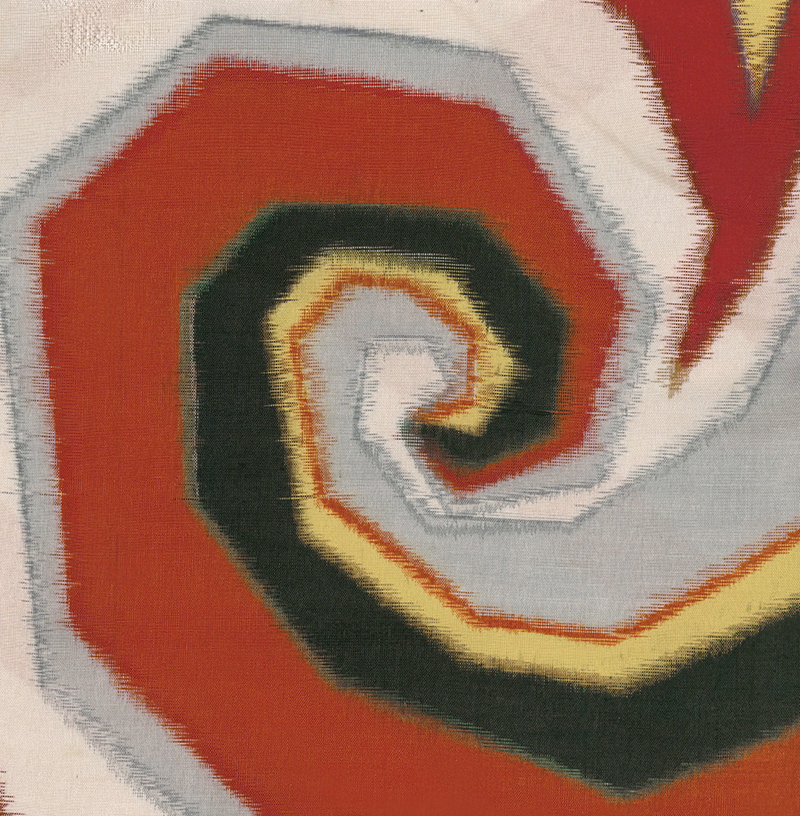

Its production involved methods reminiscent of kasuri, a traditional tie-dye technique where individual threads were dyed before weaving. In meisen production, all the warp threads were laid out and held in place with a few temporary weft threads. The warp threads were then stencil-dyed using nassen, a dye in resist paste technique. One stencil was used for each color, so they were dyed up to 5 times. After dyeing, the warps were transferred onto a weaving loom, and the cloth was woven up on hand or power looms. The technique of stencil dyeing at the thread stage enabled far more complex patterns to be created than before. Also, a wider variety of colors could be used than are found in handmade kasuri. The meisen production process involved several treatments that allowed this leftover silk to be both more durable and yield bolder colors.

The first authentic stencil-dyed meisen fabric was produced in Chichibu, north of Tokyo, in 1887; and it was this mountainous area of northern Kanto (Tokyo and surrounding areas) that continued to be at the forefront of meisen kimono production during the early to mid 20th century. Textile research centers in Kiryu, Ashikaga, and Isesaki played a key role in advancing meisen design during the 1920s and 1930s, working closely with associations in Tokyo and Kyoto to further enhance the artistic possibilities of this unique silk fabric.

For the first twenty years or so of production, meisen kimonos were largely for domestic use, and were sombre-colored and patterned with simple and restrained patterns such as stripes and small cross ikat motifs. Schoolgirls in the Kanto region were asked to wear meisen kimonos as their school uniform—often decorated with yagasuri (arrow feather) motifs. During the Taisho period, Tokyo department stores, eyeing a market opportunity for an inexpensive fashionable kimono for the flourishing middle class urban female, invested heavily into meisen kimono production, design, and marketing. These efforts yielded meisen kimono designs that became larger and bolder—eye-catching, often floral, modern designs—that were taken from both indigenous and Western art movements such as Art Nouveau and Art Deco. Meisen kimonos were more affordable than any other silk fabric on the market, becoming the favored informal, everyday garment. Each season, the department stores would present a new line of meisen kimono, and so during the 1920s and 1930s, they became the popular domestic haute couture.

Several types of meisen emerged over the years, each showcasing unique dyeing techniques. Hogushi-gasuri, for instance, involved printed or dyed warp threads that were partially unwoven and then re-woven to create soft-edged patterns, while heiyo-gasuri employed ikat dyeing on both warp and weft threads for a more interlocking design. Hanheiyo-gasuri used ikat only in select areas of the fabric, blending crisp and blurred elements. Yokoso-gasuri focused on dyeing only the warp threads, creating linear patterns running vertically through the textile. In addition, some meisen textiles incorporated an omeshi element, using hard-twisted silk to give the fabric a slightly textured, crinkled appearance. Meisen fabrics that include an omeshi element combine the vibrant designs of meisen with the textured, slightly crinkled appearance of omeshi, adding depth and structure to the garment.

Meisen comprised approximately half of Japan's production of silk kimonos during this period, as women became enamoured with their relative low cost, durability, and the adventurous designs. During the 1920s and the following several decades, roughly 70% of all Japanese women possessed at least one meisen kimono. Meisen production almost ceased during the Second World War, but enjoyed a resurgence in the 1950s. However, by 1960, large-scale producers had gone out of business, leading to a sharp reduction in its availability. From the 1960s onward, meisen was produced only on a limited basis in small workshops, as it gradually fell out of favor. The once-thriving industry that had catered to the mass market was now sustained by artisanal efforts, preserving the traditional techniques in more niche, localized settings.

This recent modest revival is due, in part, to the arrival of several exhibitions of, and publications about, meisen kimonos created in the 1920s to the 1950s. Once very affordable, meisen kimonos are presently created in small runs, selling at prices only the wealthiest can afford.

.avif)