The Evolution of Women’s Haori, from Tradition to Modern Fashion

The haori—a lightweight, open-front jacket typically made of silk—is one of Japan’s most distinct garments. Designed to be worn over a kimono, the haori differs structurally from the kimono in several key ways. While the kimono’s overlapping front panels are secured with a sash (obi), the haori’s front panels do not meet and are held together instead by a pair of short inner cords (himo). The collar of the haori, thinner and flat-laying, continues uninterrupted to the hem, unlike the kimono’s collar which ends at the waist. Women’s haori were produced in various lengths—hip-length (Cha Haori), mid-thigh (Chū Haori), and knee-length (Naga Haori)—each aligned with changing fashion trends across generations.

Origins in Masculine Dress

Although now closely associated with women’s attire, the haori originated in male dress. Its development is linked to two garments from Japan’s medieval past. One theory traces its roots to the dofuku—a functional overcoat worn by samurai during the Sengoku period (1467–1568), especially in its sleeveless jinbaori form. These coats, often made from luxurious or imported textiles, conveyed wealth and allegiance. An alternate theory connects the haori to the kataginu, a short-sleeved vest from the Muromachi period (1336–1573).

By the 17th century, the haori had evolved into daily wear for samurai and formal attire for townsmen. In the 18th century, the formal black montsuki haori, adorned with five family crests, emerged as a status symbol among samurai and merchants. Though the black montsuki eventually became the dominant form of formal male dress, men’s haori also appeared in other colors, from earthy tones and indigo to later additions like red and purple. The evolution in men’s haori colors and patterns mirrored shifting social roles and tastes, with samurai favoring restrained palettes and merchants embracing more decorative styles.

The Meiji Restoration of 1868 marked a turning point in Japanese dress. The end of the rigid feudal class system allowed broader segments of society to adopt garments like the black montsuki haori, which was formalized by government decree in 1871 as appropriate ceremonial attire. Simultaneously, Japan’s encounter with Western fashion led to black becoming associated with dignity and formality in both traditional and Western styles.

Women Begin Wearing Haori

Women’s adoption of the haori began cautiously in the late 18th to early 19th centuries, initially in specific cultural contexts. Geisha in Edo’s Fukagawa district, known for their modest and unembellished aesthetic, are thought to be the first women to wear haori. These tatsumi geisha dressed in subdued greys, often went barefoot, and sometimes took on male names—an aesthetic that extended to their understated haori jackets. Their example gradually influenced courtesans and entertainers in other districts, though widespread use by women outside these circles remained limited due to societal expectations and restrictive dress codes.

By the late Edo period (1850s–1860s), some women from merchant families began wearing haori informally or at home. The weakening of the Tokugawa regime and the loosening of sumptuary laws allowed greater sartorial freedom, and the garment’s popularity among women slowly expanded.

The Rise of the Women's Haori: 1860s–1920s

Photographs and visual records from the 1860s through the 1880s reveal the earliest styles of women’s haori. These early examples, which can be termed “heritage haori,” were typically simple in design. Monochrome or striped patterns in plain weave or modest kasuri (ikat) designs were common. Color palettes leaned toward muted tones. While men had long worn formal black haori, similar styles for women appear in visual documentation only by the 1890s.

A dramatic shift occurred in the final decade of the 19th century. A new visual language emerged in women’s haori—what can be called the “nouveau haori” style. These garments departed from the earlier restraint and embraced vibrant color combinations, pictorial scenes, and intricate surface decoration. This transformation did not immediately replace older styles; for decades, the heritage and nouveau styles coexisted. Only by the 1920s did the nouveau style come to dominate urban fashion.

The increasing presence of women in public spaces—shopping, visiting, and socializing—helped spur the popularity of these visually striking haori. During the Taisho period (1912–1926), haori became an essential outer garment for city women. Their popularity was reinforced by women's magazines and department store campaigns, which promoted the haori as a modern, elegant accessory.

Design Evolution: Taisho to Late Showa Period

The designs of women’s haori continued to evolve dramatically from the early 20th century through the postwar years. The haori featured in this publication provide a chronological lens through which this development can be examined.

Taisho Period (1912–1926)

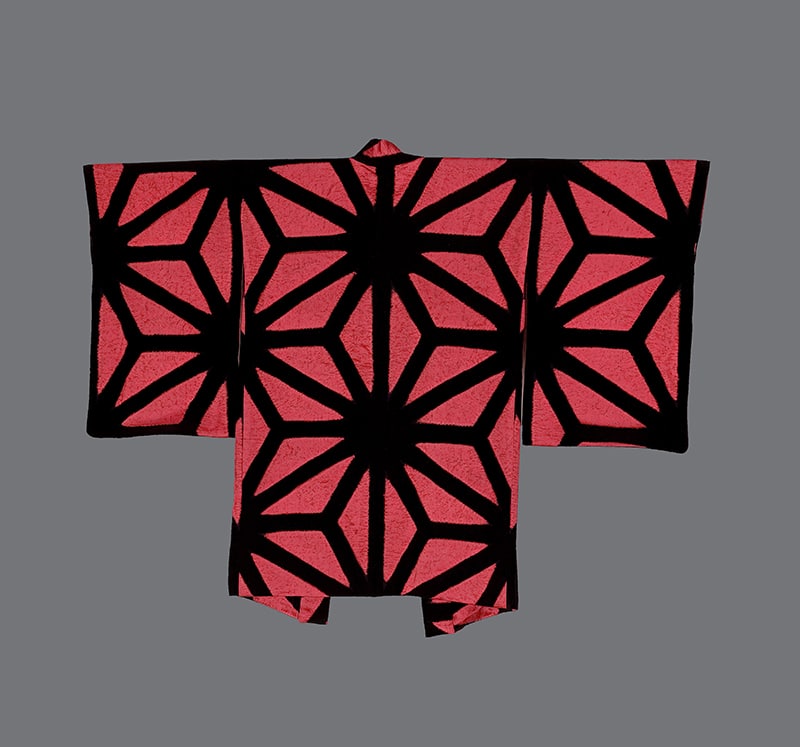

Haori from the Taisho period are characterized by bold colors and large-scale motifs. Nearly one-third employed yuzen painting techniques, while shibori (tie-dye) appeared in about a quarter. These garments integrated both traditional Japanese motifs and modern Western styles, particularly Art Nouveau and Art Deco. Lining colors were often vibrant red or red accented with secondary hues.

Early Showa Period (1926–1940)

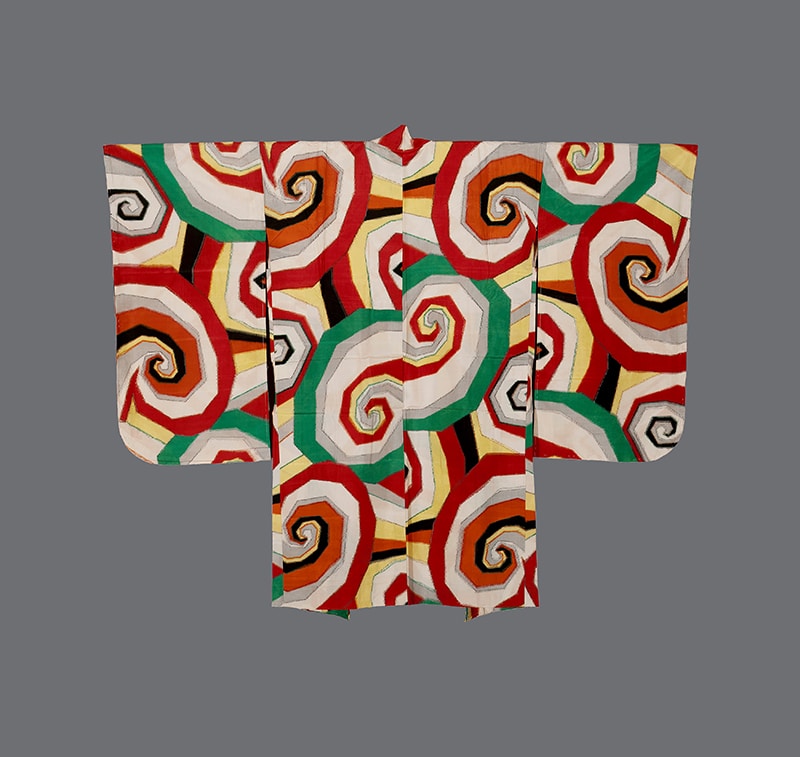

In the early Showa era, designers expanded their creative vocabulary. Shibori became more prevalent, and yuzen painting continued to be widely used. Art Deco’s geometric influence became more pronounced, resulting in bolder, abstract compositions. Industrial advances introduced synthetic materials like rayon into textile production. Linings also became more diverse in color and pattern.

Mid-Showa Period (1940–1960)

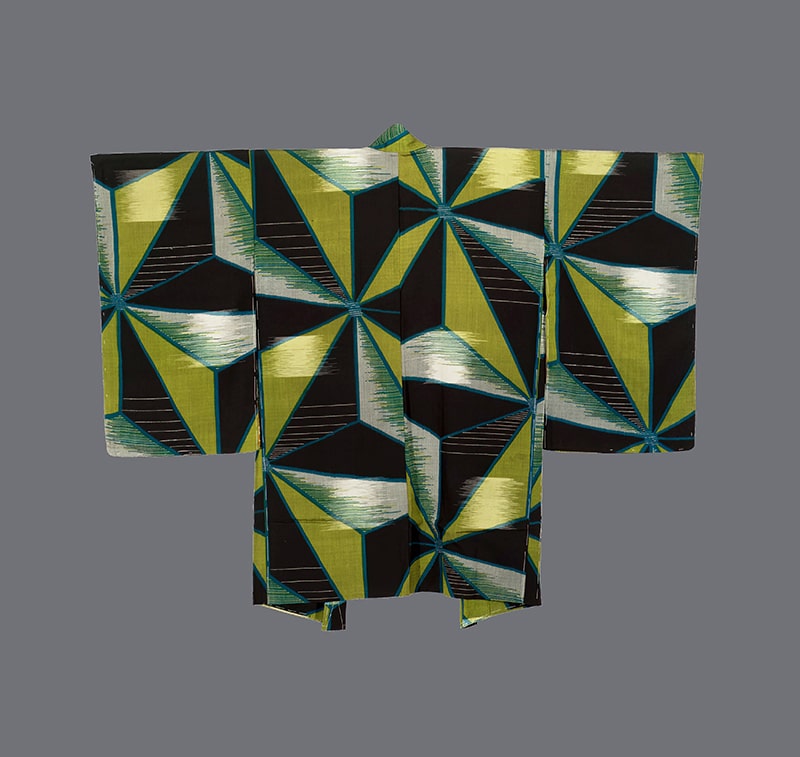

Designs from the mid-Showa period reflect the influence of Western modern art, particularly Op Art and geometric abstraction. Patterns grew more graphic and colorful. The use of kata-yuzen (stenciled yuzen) and meisen (machine-printed warp-patterned silk) became common, each accounting for about a fifth of the period’s haori. Lining colors broadened to include white and complex mixed tones.

World War II had practical consequences for women’s clothing. As women assumed industrial and labor-intensive roles, shorter haori became popular for ease of movement. These shorter styles, especially the Chū Haori and Cha Haori, remained fashionable into the postwar decades.

Late Showa Period (1950–1970)

In the final two decades of the Showa era, haori designs became increasingly abstract and experimental. Meisen silk dominated production in the 1950s, appearing in over half of the decade’s haori. Influences from psychedelic art, Pop Art, and Abstract Expressionism gave rise to garments with clashing color schemes and dynamic, sometimes disorienting patterns. Kata-yuzen and meisen continued to be the primary methods for applying pattern, blending modern visual culture with Japan’s deep textile tradition.

By this time, the haori was no longer confined to its historical role as functional outerwear—it had become a canvas for fashion-forward design and a marker of evolving gender roles and social mobility.

.avif)