The Fabric of Culture: Traditional Japanese Weaving Techniques and Their Modern Legacy

Throughout Japan's long history, artisans have continuously adapted and perfected an extensive array of weaving methods to produce the exquisite textiles that form the foundation of kimono culture. Archaeological evidence from the Jomon period (14,000-300 BC) reveals the earliest instances of basic textile production in Japan, utilizing fibers extracted from tree bark and hemp plants. The subsequent Yayoi period (300 BC-300 AD), heavily influenced by Chinese and Korean cultural exchanges, witnessed the introduction of advanced weaving practices and superior fibers including ramie and silk, materials better suited to the poncho-style garments worn by the agricultural communities of that era.

Cultural and commercial connections with technologically advanced Chinese civilizations profoundly shaped Japanese textile production during the millennium spanning the 6th to 16th centuries, introducing increasingly complex manufacturing techniques. Cotton cultivation finally established itself in Japan during the late 1500s, eventually becoming the preferred material for everyday garments over subsequent centuries. This period also saw the arrival of Chinese multi-harness and improved draw looms, enabling Japanese artisans to create sophisticated silk textiles such as rinzu (damask) and shusu (silk satin), previously obtainable only through Chinese imports.

The Edo period (1603-1868) marked an era of national isolation during which Japan largely cut itself off from external influences, fostering a time of silk craft refinement and expanding weaving mastery centered in Kyoto's Nishijin district. Japan's reopening to Western influence during the Meiji era (1868-1912) brought the importation and integration of Industrial Revolution innovations, including synthetic dyes and mechanized looms, dramatically transforming both the production speed and manufacturing costs of kimono textiles. Despite rapid modernization, traditional manual techniques and craftsmanship endured, as demand persisted for maintaining uniquely Japanese aesthetic sensibilities that only conventional methods could satisfy.

Primary Textile Materials

Bast Fibers ("Asa"): Ramie and Hemp

Ramie, derived from Chinese nettle plant stalks, creates a robust and enduring fiber naturally resistant to bacterial growth, mildew, and insect damage. Hemp, another widely used plant-based fiber, possesses comparable characteristics to ramie. Before Japanese cotton cultivation emerged in the 16th century, ramie and hemp served as the primary materials for common people's everyday clothing, while costly silk remained exclusive to aristocratic classes. The Edo period featured a premium ramie variety called 'jōfu' from Okinawa, occasionally used for upper-class summer garments. Local production of bast-fiber kimonos continued on a modest scale until modern times.

Cotton

Originally indigenous to India, cotton began displacing ramie and hemp from the 16th century onward, offering advantages in processing ease and transportation convenience while providing superior softness, warmth, and flexibility compared to bast-fiber textiles. While ramie and hemp processing could be managed at family and community levels, cotton processing and distribution required more sophisticated systems, leading most Edo-period residents to purchase rather than manufacture their clothing. Cotton remains prevalent in Japan for informal, unlined summer kimono known as 'yukata' and for everyday work garments in rural areas.

Silk

Silk represents a strong, lightweight, supple, and luxurious fabric created from silkworm caterpillar cocoons. Its celebrated luster results from triangular-shaped fibers that refract light like prisms, combined with protein layers that create a pearl-like sheen. China's Yangshao culture first cultivated silk between 4000-3000 BC, maintaining a strict imperial monopoly for two millennia. Japanese success in acquiring silkworm eggs and basic sericulture knowledge came around the 3rd century AD. Seeking to emulate Chinese and Korean aristocratic refinement, the Japanese Court provided land grants and special privileges to Chinese and Korean silk weavers willing to relocate to Japan. Over subsequent centuries, Japanese sericulture methods advanced significantly, achieving recognition by the Edo period for producing the world's finest silk quality. This excellence, combined with Meiji-period sericulture modernization, positioned Japan as the global leader in silk production—by the early 20th century, Japan generated approximately 60% of worldwide raw silk output. Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, silk remained the preferred material for ceremonial and formal kimono, with increasing popularity for informal kimono during the late Meiji, Taisho (1912-1926), and early Showa (1926-1940) periods.

Rayon

Rayon is a semi-synthetic, silk-like material manufactured from wood pulp. Invented in France during the 1880s, rayon became commercially available in Japan by 1918, where it earned the name 'jinken' (artificial silk). Japan rapidly emerged as the world's largest rayon producer, as this silk alternative offered distinct benefits: rayon avoids clinging to the body in humid conditions, demonstrates greater resistance to light-induced weakening, and requires simpler cleaning and maintenance. However, silk maintains superiority in softness, heat retention, and lustrous appearance. Due to these properties, jinken gained popularity for creating translucent summer kimono during the 1920s and 1930s. Other summer and all-season kimono of this era featured rayon-silk blends (silk warp with rayon weft) to combine the optimal qualities of both materials.

Polyester

Polyester, a synthetic petroleum-derived product, was developed in Britain in 1941 as another silk substitute. Polyester fabric offers relative wrinkle resistance, durability, easy maintenance, and significantly lower costs than silk. However, polyester provides inferior breathability compared to silk, can become uncomfortable in humid summer conditions, and carries an artificial, plastic-like texture. A minority of post-war kimono utilized polyester or polyester-natural fiber blends, with polyester inner linings being somewhat more common.

Weaving Techniques and Patterns

Fundamental Weaving Methods

Woven textiles are constructed by interlacing vertical (warp) and horizontal (weft) threads using a loom. Two of the most ancient and basic techniques include hira-ori (plain weave), where warp and weft threads alternate crossing every other line, and aya-ori (twill weave), where two or more warp threads cross an equal number of weft threads, creating a subtle diagonal pattern.

Gauze Weaving: Sha, Ra, and Ro

Several gauze weaving methods reached Japan in the 8th century AD through Middle Eastern and Chinese influences. Japanese terminology for these gauze techniques includes 'karami-ori' (entwine weave) or 'mojiri-ori' (movement weave), subdivided into three categories: 'sha,' 'ra,' and 'ro.' Unlike conventional weave structures with parallel warps intersecting wefts at right angles, gauze weaves shift the warps to cross each other, creating spaces between weft threads. Sha, a plain gauze weave, represents the simplest form, producing relatively crisp, rigid fabric. Ra constitutes a complex gauze weave employing diagonal warp threads, with warp and weft capable of combination in various ways, enabling weavers to create highly intricate patterns.

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, Japanese artisans utilized the soft and flexible ro gauze technique more frequently than sha or ra. Ro features alternating stripes of airy, open-'eye' gauze and densely woven plain sections, creating characteristic semi-transparent gauze stripes. Ro developed in Japan later than sha or ra, becoming established during the 18th century, coinciding with yuzen resist-dye painting development, as the two techniques complemented each other perfectly. Ro fabric served for numerous summer kimono types, including tomesode (formal summer kimono) and children's ceremonial garments. These summer kimono remained unlined, with the sensation of air flowing through the open gauze weave considered both physically cooling for the wearer and mentally refreshing for observers. As ro proved quite expensive, it remained a luxury item; as the 20th century progressed, affordable lightweight cotton yukata became a popular summer alternative to ro silk kimono.

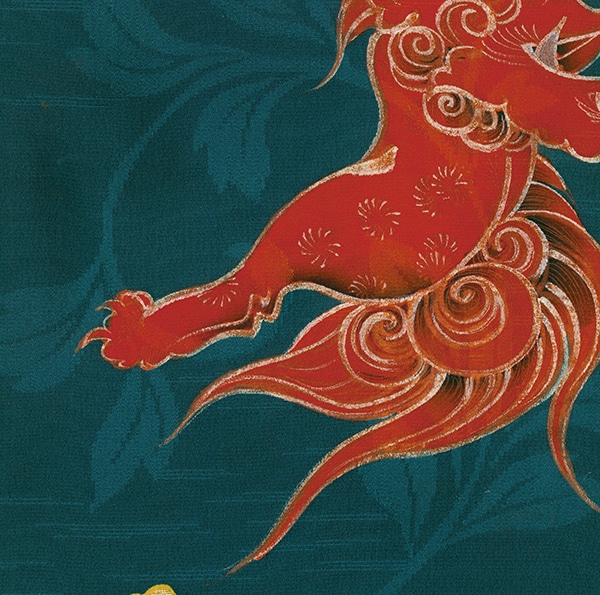

Nishijin Weaving: Weft-Faced Brocade

Contrasting with airy gauze weaves, 'nishijin-ori' (west-position weave) represents a weft-faced brocade type that ranks among the heaviest and warmest Japanese weaves. Nishijin-ori demands considerably more time and labor compared to most alternative weaving techniques.

A Japanese family returning from China during the 5th or 6th century introduced Nishijin weaves to Kyoto. During the 8th century, when Kyoto became Japan's capital, nishijin fabric established itself firmly as a premium product for Court and aristocratic use. Later, this fabric found application in Noh theater costumes. The 'nishijin' designation began during the 15th century, referencing the Nishijin district of Kyoto where weaving workshops concentrated. A popular nishijin variation called 'nishiki' involves multicolored threaded drawloom-woven fabric featuring complex motifs resembling intricate embroidery. Nishiki-woven fabrics gained popularity for creating thick, wide sashes called 'obi' and for uchikake (wedding robes). A typical nishiki weave consists of silk twill-weave foundation with silk discontinuous supplementary patterning wefts secured with supplementary warps in twill-weave construction.

Shusu Weaving: Satin

The smooth and lustrous shusu (satin) weave originated in China over two millennia ago and likely reached Japan during the 7th or 8th century. Traditional Japanese shusu employs a warp-faced weaving technique where warp yarns 'float' over weft yarns; these floats create uniform sheen, as reflected light experiences less scattering compared to other weaves, resulting in a lustrous, smooth surface. During Japan's 19th and early 20th centuries, the two most popular shusu fabric colors were black and deep blue. While shusu found frequent use in fukusa (gift cloths) and obi, the fabric also served for some uchikake, where applied embroidery formed the primary decorative element.

Rinzu Weaving

Rinzu, a monochrome figured satin silk weave similar to damask, utilizes different silk thread types for warp and weft. Rinzu fabric displays three-dimensional effects through light reflection patterns in the monochrome design, creating a double design with dyed, painted, or embroidered decoration overlaying the damask pattern. The intricately woven rinzu motifs, matching brocade complexity, require substantial skill and expertise, making rinzu among the most expensive Japanese silks.

Initially imported from China beginning in the 14th century, renowned Nishijin weavers of Kyoto began producing this luxurious cloth by 1615. At this time, rinzu fabrics predominated in men's clothing, but by the late 17th century, the fabric began appearing in upper-class women's garments. During the early to mid-Edo period, rinzu patterns remained very small, gradually enlarging by the late Edo period. Initially woven on draw looms, most production transitioned to more efficient European Jacquard looms by the late 19th century.

Chirimen and Kinsha: Crepe Plain Weaves

'Chirimen' and 'kinsha' represent plain weaves possessing crinkled, crepe-like texture and matte appearance achieved by over-twisting weft threads during weaving. The primary difference between kinsha and chirimen involves less twist in weft threads, resulting in smoother texture and crisper lines. Chinese introduction of chirimen and kinsha techniques occurred in the 16th century; however, they gained prominence in Japan only during the late 17th century, as their textured matte surface provided an excellent foundation for the newly developed yuzen resist-painting technique. Chirimen or kinsha kimono drape exceptionally well and resist creasing. Chirimen continued production during the second half of the 20th century, albeit to a lesser extent, while kinsha production rarely occurred after the mid-20th century.

Tsumugi: Pongee

'Tsumugi' (pongee) represents a sturdy plain-weave, hand-spun and handwoven fabric sourced from leftover silkworm cocoon floss scraps. While technically silk, tsumugi fabric resembles cotton in appearance. Its charming rough, uneven, nubby texture results from irregular thread widths and numerous tiny knots created by twisting and joining short scrap fibers during spinning. A renowned tsumugi characteristic involves becoming softer with increased use and washing, as spinning-applied starch gradually disappears.

Tsumugi originated in Edo-period countryside, when governmental decrees prohibited silk wearing by anyone outside noble or samurai classes. Tsumugi silk, unmarketable and cotton-like in appearance, provided a sturdy fabric allowing farmers to cleverly circumvent these strict regulations. Often created at home, the fact that the same person might spin thread, weave cloth, and sew and wear a kimono lends tsumugi esteemed uniqueness. One kimono required approximately one month to spin due to the time needed for frequent short thread joining. Striped and checked patterns remain common on most tsumugi kimono, which maintained popularity among farmers and town merchants until the mid-20th century. As creating tsumugi fabric involves elaborate and time-consuming processes, recent decades have seen tsumugi kimono become elite garments worn by the wealthy.

Kasuri: Simple Ikat

The tie-and-resist (ikat) 'kasuri' ('to blur') technique apparently originated across multiple continents over one or two millennia ago, spreading to most Japanese regions via Okinawa by the Edo period. Cotton served as the preferred kasuri fiber, though silk was occasionally used. The kasuri technique involves selectively binding and dyeing portions of warp or weft threads, or sometimes both, before weaving the fabric. Bound thread sections remain undyed, creating patterns against the dyed background when woven. One popular kasuri technique called 'tate-gasuri' involves dyeing warp threads. A less common method is 'yoko-gasuri,' where only wefts receive dyeing; finally, the extremely complicated 'tate-yoko-gasuri,' a double kasuri found in Okinawa, involves dyeing both warps and wefts. Since cotton threads never align perfectly, resulting patterns feature pleasing soft, blurred edges. Dark blue extracted from indigo plants provided the most commonly used kasuri dye. The most popular kasuri variety has always been 'kon-gasuri' ('to blur blue'), characterized by white patterns on dark blue backgrounds. Cotton kasuri fabrics, extremely rugged and durable, appear mainly in Japan's countryside, where farmers' wives would weave ikat work garments for their families. Geometric patterns dominate kasuri fabrics, with popular motifs including crosses and crosses enclosed in kikko (tortoise) lattice. When pictorial motifs appear, they typically combine with geometric patterns.

Omeshi: Pre-Dyed Crepes

During the 1880s, Japanese inventor Iwase Kichibei developed a water-powered spinning machine capable of producing highly twisted silk yarns, which combined with recently imported Jacquard looms, could weave a new crepe cloth type called 'omeshi' ('being worn by noble persons'), a heavy crepe silk woven with strongly twisted pre-dyed threads. In contrast, chirimen crepe receives dyeing after weaving. The first popular omeshi variety was reversible figured crepe called 'futsu-omeshi,' which the 1890s saw superseded in popularity by a supplementary embroidery-like weft-patterned variety called 'nuitori-omeshi.' Other omeshi varieties include 'shima' (striped) and 'Majolica' (with lamé threads). Futsu, nuitori, and Majolica omeshi kimono are relatively stiff and thick due to their complex construction, ranking among the highest-value pre-dyed silk kimono, suitable for both informal and semi-formal occasions.

Many omeshi kimono varieties were created during the first four decades of the 20th century, while the second half saw decreased variety. By the 20th century's end, the main omeshi production focused on monochrome or minimally patterned fabrics. The final brief omeshi heyday occurred with the 1959 development of complex Majolica omeshi technique, reaching peak sales in 1962. Majolica omeshi combined weft kasuri and jacquard weave techniques while incorporating metallic lamé threads. This colorful and intricate creation proved ideal for generating large European-influenced pictorial embroidery-like images on fabric.

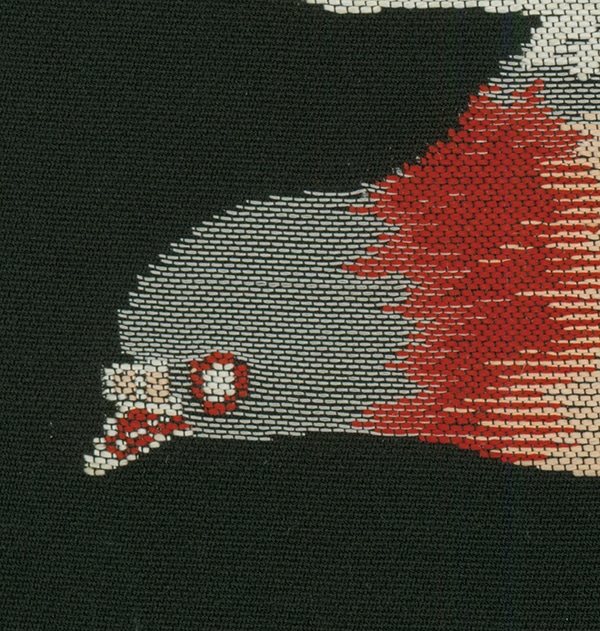

Meisen: Pongee Silk Ikat

Concurrent with omeshi invention and rise came another new Japanese fabric that would profoundly impact the Japanese kimono industry—'meisen.' This refers to an inexpensive, thickly woven and glossy fabric with stiff drape, produced from reeled low-quality silk, with patterns possessing the slightly blurred appearance of very complex kasuri. The meisen production process involved several treatments enabling this leftover silk to become both more durable and yield bolder colors.

The first authentic stencil-dyed meisen fabric was produced in Chichibu, north of Tokyo, in 1887; this mountainous northern Kanto region (Tokyo and surrounding areas) continued leading meisen kimono production during the early to mid-20th century. For approximately the first twenty years of production, meisen kimono were largely for domestic use, featuring somber colors and simple, restrained patterns such as stripes and small cross ikat motifs. Kanto region schoolgirls were required to wear meisen kimono as school uniforms, often decorated with yagasuri (arrow feather) motifs. During the Taisho period, Tokyo department stores, recognizing a market opportunity for inexpensive fashionable kimono for the flourishing middle-class urban female population, invested heavily in meisen kimono production, design, and marketing. These efforts produced meisen kimono designs that became larger and bolder—eye-catching, often floral, modern designs—drawn from both indigenous and Western art movements such as Art Nouveau and Art Deco. Meisen kimono were more affordable than any other silk fabric on the market, becoming the favored informal, everyday garment. Each season, department stores would present new meisen kimono lines, making them the popular domestic haute couture during the 1920s and 1930s.

Meisen comprised approximately half of Japan's silk kimono production during this period, as women became enchanted with their relative affordability, durability, and adventurous designs. During the 1920s and following decades, roughly 70% of all Japanese women owned at least one meisen kimono. Meisen production nearly ceased during World War II but enjoyed a resurgence in the 1950s, after which popularity declined until the early 21st century. This recent modest revival stems partly from exhibitions and publications about meisen kimono created from the 1920s to 1950s. Once very affordable, meisen kimono are presently created in small runs, selling at prices only the wealthiest can afford.

.avif)