This extraordinary chirimen silk kimono represents a poignant cultural intersection between Okinawan bingata traditions and Japanese aesthetic assimilation following the annexation of the Ryukyu Kingdom. The garment embodies the complex artistic negotiations that occurred as Okinawan artisans adapted their sophisticated textile heritage to conform with mainland Japanese practices while preserving elements of their distinctive cultural identity.

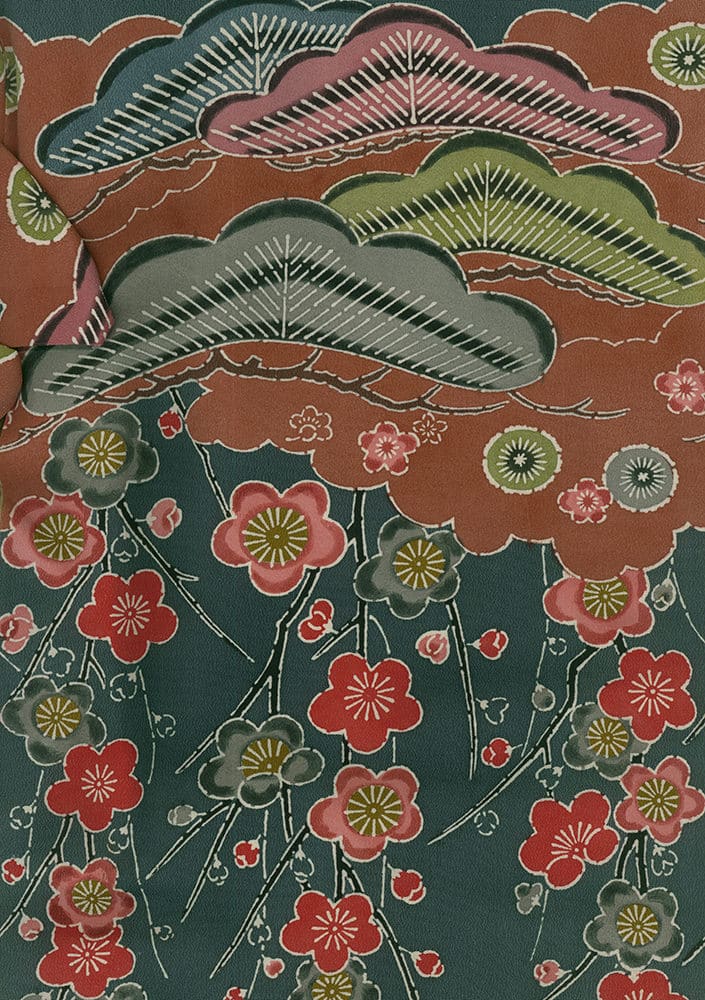

The technical achievement of this piece lies in its masterful adaptation of traditional bingata stenciling and resist-dyeing techniques to create a design that superficially resembles contemporary Japanese kimono patterns. The bingata process, which developed through centuries of cultural exchange with China, India, and Java, employed complex layered stenciling methods that allowed for the intricate color gradations visible in the pine tree and floral motifs. The coral-pink ground of the upper section transitions seamlessly into the deep teal-green body, demonstrating the sophisticated color theory that bingata artisans had perfected by this period. The resist-dyed cherry blossoms scattered across the composition show the characteristic soft edges and subtle color bleeding that distinguish bingata from other Japanese dyeing methods.

The design layout reveals a careful balance between Okinawan decorative traditions and Meiji-period Japanese sensibilities. The upper section features stylized pine trees rendered in the traditional Okinawan palette of coral, green, and gold, interspersed with scattered floral medallions that reference Chinese decorative vocabulary. The main body presents cascading cherry blossoms and iris motifs arranged in naturalistic clusters, while the hem displays a formal border of iris flowers emerging from flowing water patterns - a composition that echoes both Okinawan court textile traditions and Japanese seasonal imagery.

The cultural significance of this kimono extends far beyond its aesthetic achievement. Created during the traumatic period of cultural assimilation following 1879, when the Ryukyu aristocracy was disbanded and Okinawan cultural practices were actively suppressed, this garment likely served as a form of cultural resistance for a wealthy Okinawan woman navigating her new identity within the Japanese empire. The subtle incorporation of pale blue silk lining, traditionally reserved for Ryukyu aristocracy, functions as a discreet homage to the former kingdom's color hierarchies. The motifs themselves carry layered meanings: while the cherry blossoms align with Japanese seasonal aesthetics, the specific color combinations maintain distinctly Okinawan characteristics that would have been recognizable to those familiar with bingata traditions, creating a visual language of cultural memory embedded within apparent conformity to Japanese imperial aesthetics.

It measures 49 inches (124 cm) from sleeve-end to sleeve-end and stands at a height of 61 inches (155 cm).

.avif)